The values of the Camino in 12 months

October 23, 1987, the Council of Europe declared the Camino de Santiago as the first European Cultural Itinerary. This distinction, which currently recognises a total of 32 routes, encouraged the recovery and development of the Camino, an example of Europeanism and a privileged meeting space.

Thirty years later, we analyse how this millennial route evolved with José Antonio Ortiz, director of the magazine Peregrino, launched that same year by the Spanish Federation of Associations of Friends of the Camino de Santiago with the aim of portraying the reality of the Jacobean pilgrim.

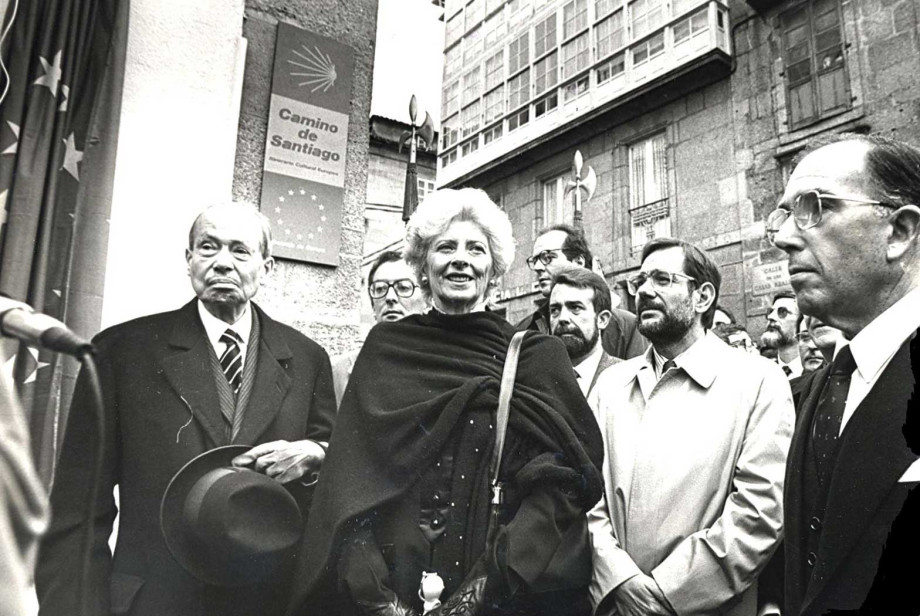

The Plaza del Obradoiro and the Cathedral of Santiago were the stages chosen to proclaim the Camino de Santiago as the first European Cultural Itinerary on 23 October 1987. The then-Secretary General of the Council of Europe, Marcelino Oreja, was in charge of reading the Declaration of Santiago de Compostela in a ceremony that reached great international projection.

The religious, cultural and European dimensions focus on a text that recognises the highly symbolic character of the Camino in the process of building Europe. "That the faith that animated pilgrims in the course of history and that brought them together in a common yearning, beyond differences and national interests, also encourages us in this age, particularly the youngest, to follow these paths to build a society founded on tolerance, respect for others, freedom and solidarity," concludes the Declaration of the Camino de Santiago.

The Council of Europe also established the need to revitalise the Camino de Santiago through six actions: to identify the Caminos de Santiago in Europe, signal the main routes through a common emblem, to restore and enhance the cultural and natural heritage, promote the culture and research of Jacobean history, promote permanent exchange between the territories through which the Camino passes and promote artistic and cultural creation that disseminates the values of common identity.

José Antonio Ortiz: “In these thirty years, it went from nothing to everything.”

The declaration of the Camino de Santiago as European Cultural Itinerary was decisive to achieve a resurgence of this pilgrimage route. "It went from nothing to something," José Antonio Ortiz says, director of, the magazine Peregrino and great connoisseur of the Camino de Santiago.

His first anecdote is very illustrative. During his pilgrimage in 1986, José Antonio Ortiz arrived in Santiago on 14 August, now one of the busiest months. "When I went to get my credential at the Cathedral, we were informed that there had been a record number of pilgrims that day. A total of 20 people had completed the Camino," he explains.

And at that time there was not massive knowledge of the Camino. Although the seeds had been sewn that would lead to its growth. People like Ortiz himself, without knowing why, had always been aware of the Camino. Or, of course, figures like Elias Valiña and his efforts to mark the Route and promote the creation of associations for work on the recovery of the Camino and pilgrimage. “The declaration of the Camino as European Cultural Itinerary was possibly thanks to the confluence of events and people,” relates the director of the magazine Peregrino.

Confluence de events and people

Three events are fundamental for José Antonio Ortiz. Firstly, the clearly European speech delivered in 1982 by Pope John Paul II in Santiago de Compostela, where he closed his visit to Spain. "At the time, very few understood the full meaning of that speech. But it clearly favoured the rise of the Camino," he says.

On the other hand, it is the very birth of the Council of Europe and the need to launch activities or symbolic actions that give content and dimension to the body.

The third part of this confluence is found in the petition that the Association of Friends of los Pazos, presided then by Juan Manuel López Chaves, sent a petition to the Council of Europe to recognise the role of the Camino de Santiago in European integration, a good example in the construction of European identity. "By chance, he also wanted the president of the Council of Europe to be a Spaniard, Marcelino Oreja, thus enabling the declaration to become reality," admits Ortiz.

The director of the magazine Peregrino recognises that the Declaration of Santiago de Compostela was a mere recommendation, without material load. In fact, the acts took place in the Obradoiro and Cathedral but a section of the Camino was not travelled, nor a small pilgrimage to Santiago.

Camino and Hospitality

In spite of everything, this recognition did contribute to the new rise of the Camino de Santiago. And not just at the influx level. In fact, if we look back, Ortiz highlights two major changes over the course of the three decades. On the one hand, the recovery of the Caminos themselves. "Years ago, there was a pilgrim consciousness but no route. You were going where you could," says Ortiz, for whom many Caminos, despite recent recovery, make the pilgrimage much easier.

And, finally, the hospitality. “Without hostels, with hospitality staff, the Camino is unthinkable. They are as necessary as a service station on the highway: to refuel you with energy. Hospitality is what facilitates becoming a pilgrim.”

Your email address will not be published.

Mandatory fields are marked with *